Scraping to Learn

You’ll find tons of tutorials about ’learning to scrape the web’, but here’s a first – scraping to learn the web.

The past few months of the lockdown have been fairly productive for me as far as learning new skills (physical or technological) goes. (Quick side note: I am not a productivity hacker, I still have really shit days, I have just been lucky to have figured out how to ride my motivation wave™).

After wishing to learn JavaScript for over 8 years, I finally did learn it and built a decent web application with it. The natural next step was to learn about the JS frameworks everyone has their knickers in a twist about. I picked Vue.js as my weapon of choice because it’s the only one whose documentation I could actually understand. I had an idea I wanted to work on for personal use which I thought was a good fit for this endeavour.

And so it began.

Buzo

The project in question is Buzo.Dog – a no non-sense internet explorer. There are a few publications that I enjoy reading and Buzo.Dog lets me find a random article from their archives and read it. Think of it as a RSS feed reader but for archives and not latest posts.

That isn’t what I started with though. Initially I wanted to build an open-source StumbleUpon clone but without the social network and with plenty more privacy. (Still working on it)

I started off by scraping links from Pinboard and Reddit. That gave me a mish-mash that tasted like gourd flavoured cookie dough – not ideal. After putting the project aside for a few days I hit on the idea of using at as a publication reader for which I have so far scraped – Vox, xkcd, Brain Pickings, Aeon, Three Word Phrase, Margins (on Substack) and Statechery. All of which put together yielded ~10,000 links (excluding Vox, I am holding on on that).

While the high level process of scraping any website is the same –

- Go to link.

- Process raw html.

- Pull relevant tags.

… each of these websites presented a slightly different learning opportunity.

In this post I talk about the process by somewhat randomly lumping the sites together – like a true internet savant. Let us begin.

xkcd, Three Word Phrase, Pinboard

This is the closest you can get to the three-step process I outlined before. All of these websites list their links on a single page that loads the full content in one go. Oh and, I was browsing the /popular page on Pinboard, which is public.

Scraping these sites was a textbook BeautifulSoup (bs4) example. Here are the steps –

-

First look at the source code of the site in question.

xkcd lumps the links in regular

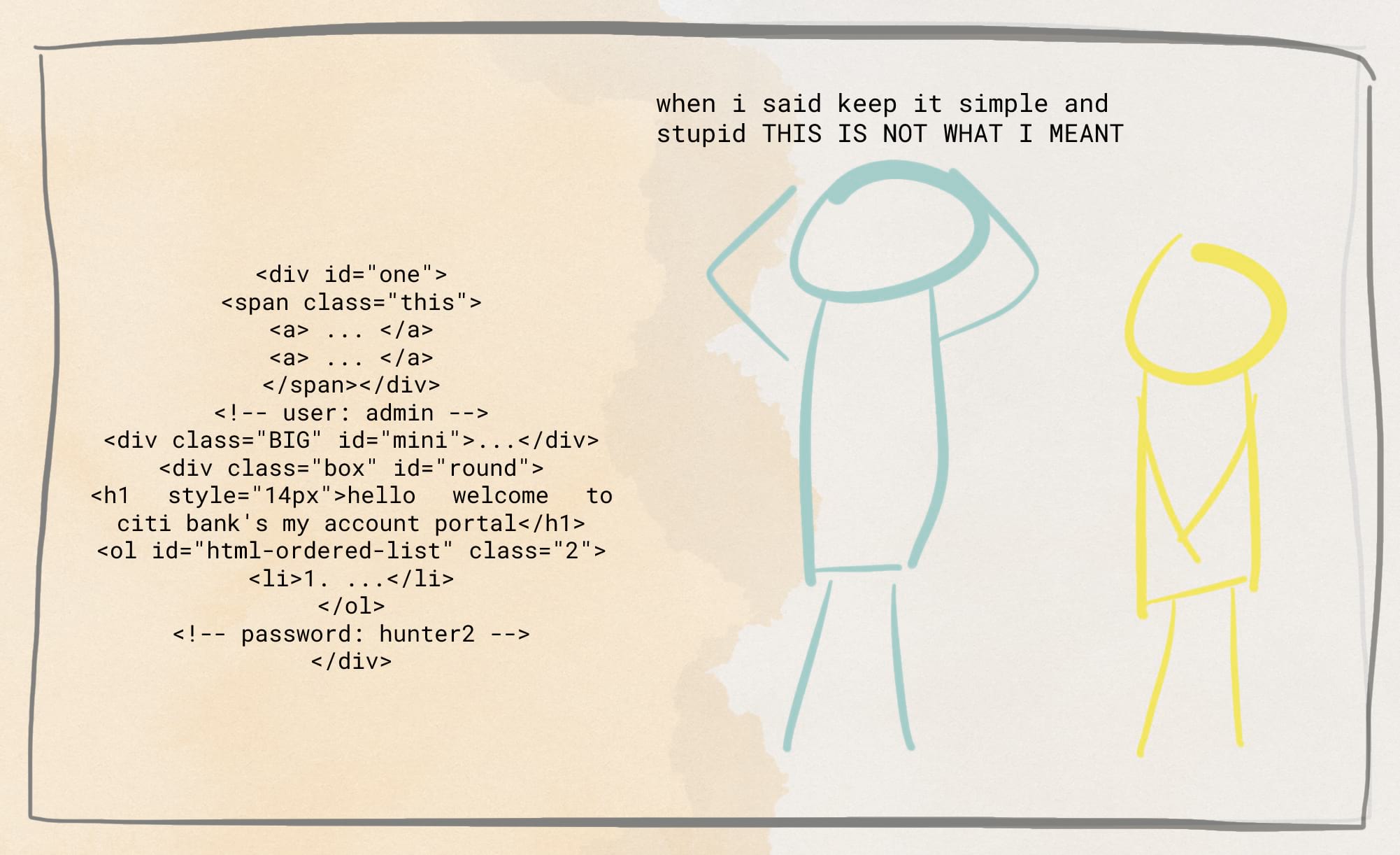

<a>tags inside of possibly the most stick-figure-esque html tag –<div id="middleContainer" class="box">Yeah. Really.

You KISS your mother with that mouth?

Three Word Phrase does something similar but in a marginally better named –

<span class="links">.Pinboard is the nicest of the lot with each link tagged with the class name

bookmark_title, settled inside of a comfy div.With this we know exactly which elements we are going to hit. So let’s hit ’em.

-

Process the raw html.

It’s fairly easy to see how these tags can be extracted using bs4 so I am going to skip that. Instead I will quickly mention how I stored the information from these tags.

I use a Mongo DB backend so naturally I am very comfortably with JSONs and Python dictionaries. For each link I scrape, I use a Python dict like this –

1 2link_meta = {'title': '', 'url': '', 'description': '', 'language': '', 'site': '', 'image': '', 'index': ''}… to add all the metadata that I can get from the source itself. Unfortunately the three sources in this section don’t offer anything beyond the title and url. But there will be more on that later.

Congratulations! So far you have learnt nothing. So let’s talk about the funny little issue I faced when scraping xkcd’s boring ass html.

You see, when you scrape a tag using bs4, you can get the contents of the tag using the .contents parameter which returns a list. To save some code, I often use .contents[0] to get the text because well, the list has just one element anyway. Neat, eh?

Not always though! One xkcd comic title has a span in it to change the colour of a word. And what does that mean? It means that the first element of .contents is now a bs4 tag type and the rest of the text is the second element. This broke my code. And it annoyed me because the comic in question is about pancakes. I love pancakes.

Brain Pickings

Moving on. This dandy website brings a new challenge – content spread across multiple pages!

This adds a tiny bit of extra work because now we have two for loops instead. The first one to cycle through all the pages and the second one to scrape all the links from that page. Fairly easy.

Interestingly the content here is arranged in two parallel divs. So I had to make two soups. Still fairly easy.

What’s to learn here then? Oh, same as with xkcd. Prepare for inconsistencies!

With a website as old as this, there are bound to be inconsistencies. I kept hitting absent images or descriptions which would make my code fail. And thus I added a try - except clause. Try to fetch the image from the site, but if you can’t just use the site’s header image instead. And if there’s no description, let it be.

Plus, I faced the same problem as with xkcd – the contents returned a tag + text combo. Not once but often. Which again is to be expected over a sample of over 4500+ links! So to accommodate this, I had to set up a try - except again.

Stratechery

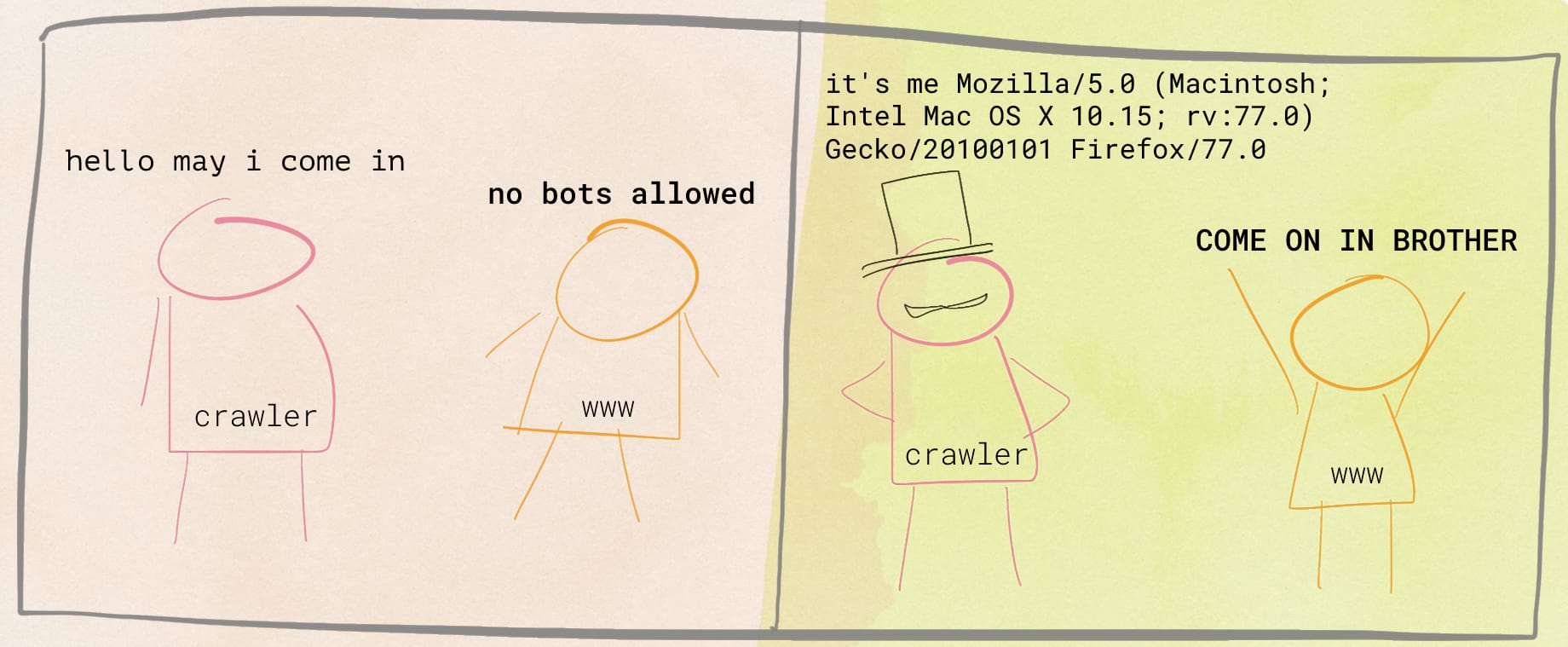

This too was fairly similar to Brain Pickings albeit with fewer tag-related problems. What I did face was a soft block. My Python crawler was greeted by a 403 Forbidden error - which means that the site admin has forbidden crawlers from accessing the site’s contents.

The workaround was fairly simple. My crawler pretended to be a user.

User agent strings attached

Margins

This is not a traditional website but a newsletter-blog hybrid that exists on Substack. And somehow I expected Substack to give me a bit of a challenge. When I requested the link with my Python crawler, I was hit by the login modal.

I investigated the archive page and saw that while the content was all listed on a single page, it used an infinite scroll mechanism to load new articles.

The modal and this scroll combined made me think twice. Luckily, this newsletter is kind of new, so there weren’t too many links and I was able to load the full list of articles manually with just a few scrolls.

And then I just copied the raw html and saved it in a new file. F*ck the police.

Lesson: Don’t make it harder than it has to be.

An interesting issue I faced when processing this data was that of “data doubling”. Instead of the 120 something tags that should’ve been, my code returned twice the number - 240. I didn’t bother investigating it much and instead just skipped every alternate tag in my loop. Keeping it simple.

A bothersome issue I faced had to do with emojis. Turns out Ranjan and Can like using emojis quite often in article titles or descriptions. Somehow MongoDB wasn’t able to figure its way around it. I tried debugging it for a short while. And then just opened the JSON and got rid of all the emojis.

Links on the Margins.

Margins has a sub-series called ‘Links on the Margins’ where the authors share a curated list of articles, videos and other internet nonsense. While I had already processed these posts as a whole, I wanted to process the links in these posts as well.

Now, how I do I find just these posts out of the entire archive? I could probably set up a check in my code where the I compare the contents of the article title against a string like “links on the margins”. But that could probably fail because this isn’t really a ‘search’, is it?

Time to make it simple: head over to Margins on Substack, use their search bar to load all the ‘Links on the Margins’ posts. Copy the rawl html to a local file.

Rinse and repeat.

Big ups to the authors for following a consistent layout in their posts. Here I had to search for all H3 tags in the post to get the shared link’s title and url. For most links the <p> tag immediately following the title had the source of the link. The only manual modification I had to make was that of ignoring the first H3 tag because that was the post’s subtitle.

Vox, Aeon

This is where infinity scroll becomes a crawler nightmare. Both Vox and Aeon’s archive pages load more articles in the same page when the user reaches the bottom of the page and clicks the ‘Load More’ button.

How do I go about this? I certainly can’t copy the raw HTML from each page because there’s hundreds of them. Do I set up Selenium then? Maybe go headless with Zombie?

I failed with both. Couldn’t even set them up. And thus I arrived at the sage reminder – everything on the internet is a network request.

Gen Z? More like Lay Z

I checked the Network tab using Inspect Element and saw that there was a clear url that was processing the requests. Life became pretty simple after that.

When you load the Vox archives you reach – https://www.vox.com/fetch/archives/2020/1 for January 2020. After which you’re supposed to use the button to load more articles which get injected in the same page.

But the network tab tells me that clicking that button makes a request to – https://www.vox.com/fetch/archives/2020/1/2. Aha!

Playing around with it, I figured that Vox follows a calendar nomenclature. If you hit /2020/6/25, you will see all the articles published on the 25th of June, 2020.

Aeon simply had a ?page= argument appended to the url.

The rest of the process was identical to the ones above.

So that’s that then. This is all that I learned from a couple of hours of web scraping (spread over many days). As I scrape more websites and cross paths with new challenges, I might add to this article or maybe create a new article.

If you’re interested in this content, I will talk about adding metadata to web links in another post. Keep an eye out.